Anne Enright: How Rough Magic put new shapes on Irish theatre

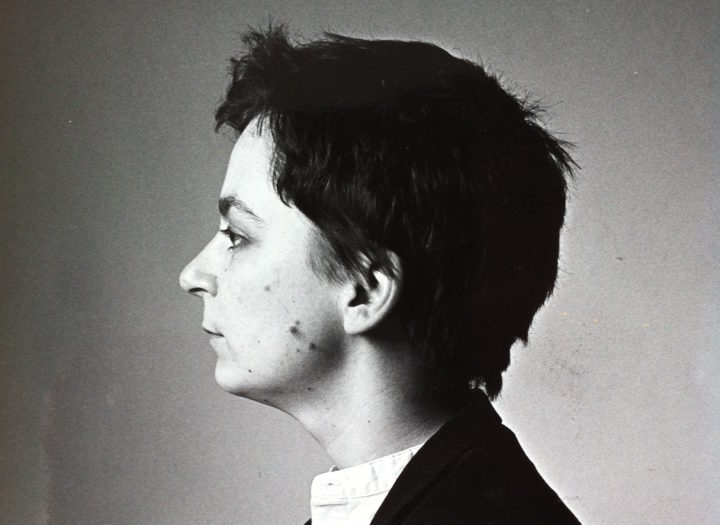

In Rough Magic’s first autumn season in 1984, I was cast as Dull Gret in Top Girls by Caryl Churchill. I wore a medieval soldier’s breastplate, which was nice. The character was based on the mad figure of a woman invading hell, as painted by Breugel the Elder. The role required me to sit on stage through a dinner scene, stuffing my face and saying “potatoes” while other historical women conducted a glittering conversation with Marlene, the central character, who was played by Pauline McLynn.

The Project Arts Centre was in a state of dilapidation that year and the place was freezing. During the day, you could look up and see the holes in the roof, little piercings of light that turned it into a sieve when it rained. The food for the dinner scene came in from the Granary restaurant next door. It was a pretend feast: a bowl of cold, thick soup that hit your stomach like bad news, washed down with ice-cold Ribena wine, of which I drank two bottles in 20 minutes. By the end of the first act I was shivering from the inside. I remember that the contents of my bladder felt cold – a sensation I have not experienced since.

Bounced

As the run progressed, it became increasingly hard to get the food down and to keep it there. One night, it bounced. I left the stage and threw it up very simply, and came on again to say “potatoes” when the moment came for my cue. This was a clear illustration of the difference between the actor’s experience and that of the audience, but I had a great time. The part appealed to my love of misrule, and Lynne Parker still laughs at my enacted peasant greed, as though it is a great joke to release, in an actor, some more original or essential self.

I started working with Rough Magic before it was Rough Magic, when it was just a clique of drinking, roaring, talented students in Players, the drama society of Trinity College Dublin. In my first year there, Lynne cast me as Everyman in the mystery play of that name. She looked at me and saw something that involved whiteface and a Pierrot hat. This was not something I had ever imagined for myself, but the casting process is not about you – or not entirely: it is an invitation to meet or become an image of yourself in someone else’s head.

To be cast by Lynne was to be puzzled and enlarged. In 1981, Lynne and Pauline ran Players, more or less, and, at the age of 19, I was often surprised by the things they knew. Pauline knew how to type, which was something you learned at night school – a complex craft that was, like knitting, most suited to the female hand. Pauline was a knitter and the daughter of a knitter, but neither mother nor daughter ever followed a pattern, so they just made it up as they went along.

Wrote to Beckett

Pauline knew how to write letters as well as how to type them and she also knew how to get them into a post box. She was competent, but she was more than that again. It is possible she wrote to Beckett, and that she got a reply. Despite these manifest and unusual talents, Pauline wanted to become an actor, a yearning that surprised me when actors were so easy to find. It was something everyone wanted to do – except, perhaps, Lynne.

The girls were room-mates in college, and a little frightening. Lynne also knew how to make clothes without recourse to a pattern. She did so with an eye to her own limitations as a seamstress, so there were no pleats or packets, no collars or lapels. One top had a simple round collar, and was made out of a stripey fabric that looked like, or perhaps was, mattress ticking. My own mother, who was often bullied by the arrows and little notches on a Simplicity pattern, looked at it very hard.

Lynne did not type, but she took notes constantly and was seldom without a pen – usually a fine-nibbed marker, the kind that cost money to buy. She chewed this pen or she waved it, stuck it behind her ear and took it out again. The pen was used to conduct the shape of some thought as it formed. She would catch this thought, quite suddenly, and jot it down, after which she looked at her notes, curling, over and over, the corner of the page. A good amount of time in the rehearsal room was spent watching Lynne think.

I had never come across this before: a person who imagines something and then conjures it out of the people in front of her. The way Lynne described what she saw – or what she wanted from you as an actor – was very compelling, as though it was already there in the room, if only you could find it.

Bauhaus design

A lot of her thinking was visual. The set for Everyman comprised a circle, a triangle and a square in pastel colours, based, she said, on Bauhaus design. The way she described it was also, somehow, a description of how I might approach the role. Lynne was a watcher and it was hard to know what she saw – nor could she tell you, until she saw it. She worked by recognition, which was often fugitive. “Hmm,” she said, and then, sometimes, “Yes!” To which you might say, “Yes, what?”

This seemed to me, at 19, to be a very adult sensibility but I think it was more probably an aesthetic one. She thought in shapes, and as such was alert to social patterns and forms. She was interested in character as a 19th-century novelist might be interested in character – not as self, that surging sense of presence the actor brings onstage, but as interaction, which is to say as comedy. Manners intrigued her. She read Austen and recommended the work of Nancy Mitford; the plays she chose were often social and always well-made. Despite the fact that we were all so young and the possibilities for cruelty abounded, emotional rawness was not her goal. She was not interested in exposing the actor or in wringing empathy from the audience. From the very beginning, Lynne was interested, as a director, in shape, circumference, balance and pleasure.

Her love of form was not casual, nor was it restrictive. Form was a way to contain and to allow the unruly ego of the actor and, later, of the writer. We were, indeed, an unruly gang. Pauline, the competent administrator, would don sideburns for the part of Mrs Doyle in Father Ted and pick up a writing career because she could do that too. Acting is a highly dependent profession and I was not the only Rough Magic actor to turn to the page (though I think I was the first).

Writers’ company

Actors, in the Rough Magic universe, were never considered to be illiterate, and many were called to write for the company over the years: Pom Boyd with Down onto Blue, Gina Moxley with Danti-Dan. It was from its genesis a writers’ company. Co-founder Declan Hughes wrote a series of plays and adaptations that set Rough Magic in an international tradition, but with an Irish accent, most notably Digging for Fire in 1991, a play in which my own urban generation found an intense voice. I will never forget the outraged self-consciousness I felt watching characters on stage whose life was so like mine, it was like being robbed. I could feel it on my skin, a rising sense of shame or fury that evaporated very simply about 20 minutes in. This was when I realised that the characters were not me – they were just like me, and the play opened out in a remarkable way. This trick also opened out possibilities for me as a future artist: it was such a gift, the revelation that I might write characters who were contemporary and near.

As a script, Digging for Fire was propelled by argument and by the need for emotional accuracy; it was explosive by nature and held together with great control by Lynne’s direction. The steady pulse of the production made the push for truth more unbearable rather than less, while careful choreography kept the tensions between the characters taut. For Lynne it was all about making slow configurations.

A concern with form also characterises the writings of Arthur Riordan; form that is, in Improbable Frequency, maddened into maze and rhyme. Lynne understood the tension between complication and transgression that marks Irish modernism or the Irish baroque. It was, for her, a question of wit. With writers, as with actors, she obliged them to be their unruly selves, requiring in each case that they also make simple and elegant narrative shapes.

Pace and shape

There is much to be said about Rough Magic’s place in Irish theatre, its role in some national or international conversation, of which these plays may be considered a part. But it is Lynne’s talent for pace and shape that is, for me, the mark of the company for over 30 years, her ability to hold and resolve conflict within the circumference of the stage.

Sadly, I was only so-so in my last Rough Magic role, when I played Aunt Dan in Aunt Dan and Lemon by Wallace Shawn. “Be more . . . fabulous,” Lynne said, and dressed me in white. I have never been fabulous in white but, more to the point, I could not enter the moral system of the play in which the character manages and manipulates someone more naive. I was always bad at that kind of thing, seeing myself, possibly inaccurately, as more naive than not. Perhaps this is why I was happy, in my first year in college, to be cast by both Pauline and Lynne as the girlfriend of a guy they knew called Martin. This was a leap of the imagination which I did not quite see at the time but which would, as it turned out, last the rest of my life. Who knew? Lynne did. She could see it working. So much depends on getting the casting right.

By Anne Enright in The Irish Times, Sat 4th January 2020.